Editor’s Note: Peter Bergen is CNN’s national security analyst, a vice president at New America and a professor of practice at Arizona State University. He is the author of “United States of Jihad: Investigating America’s Homegrown Terrorists.” For more analysis of the jihadist threat today read this paper by Peter Bergen.

Story highlights

For Osama bin Laden, September 11 was a great tactical victory but a huge strategic failure, writes Peter Bergen

15 years later, US still embroiled in the Mideast, despite bin Laden's aim of reducing American involvement, he says

The mistake made by George W. Bush in launching the Iraq War also looms large, Bergen says

Like the attack on Pearl Harbor, another hinge event in American history, 9/11 was a great tactical victory for America’s enemies. But in both these cases the tactical success of the attacks was not matched by strategic victories. Quite the reverse.

The Japanese scored an important victory at Pearl Harbor, but the attack pulled the United States into World War II and four years later Japan was in ruins, utterly defeated.

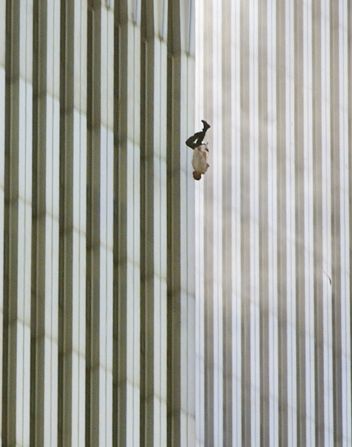

Similarly, al Qaeda’s attacks coming out of the azure-blue sky 15 years ago, on Tuesday morning September 11, 2001, were a great shock to Americans and, indeed, to much of the world: Almost 3,000 dead; many hundreds of billions of dollars of damage to the US economy, and the shock of the world’s only superpower being taken on by a relatively small terrorist group, al Qaeda. Not since the British had burned down the White House in 1814 almost two centuries earlier had America’s enemies succeeded in attacking the continental United States.

For so long the two great oceans of the Atlantic and the Pacific had protected America from its enemies, but no more.

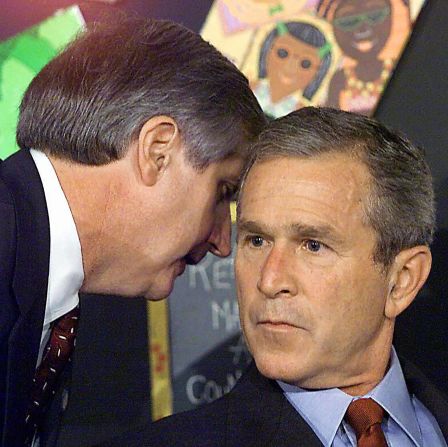

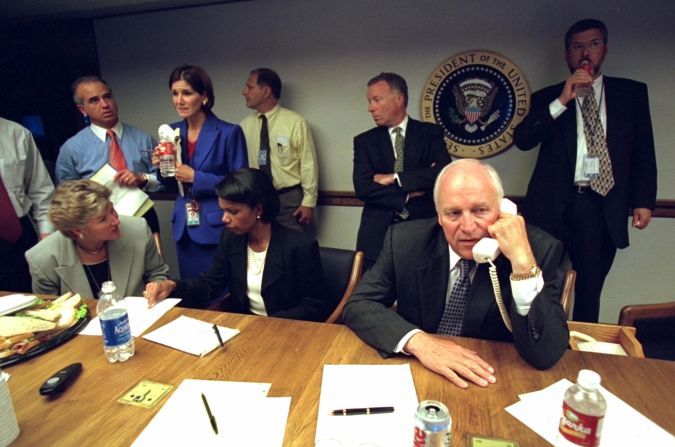

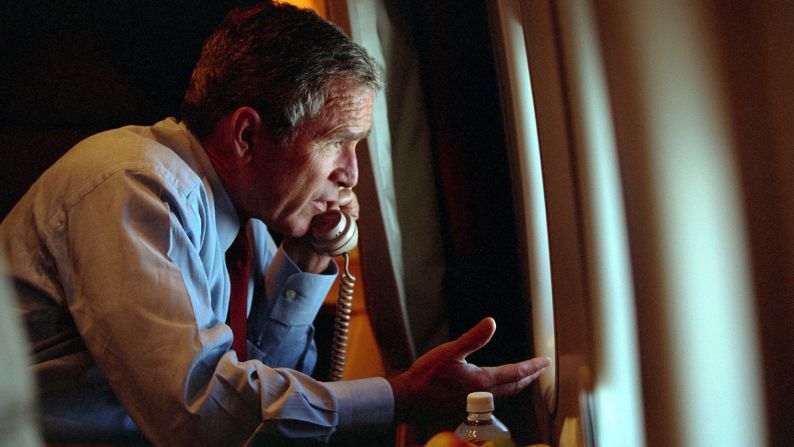

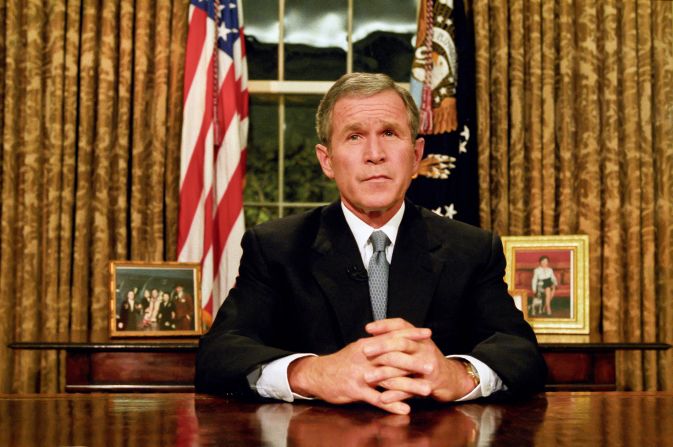

In photos: The September 11 attacks

Yet, for all their tactical success the 9/11 attacks failed strategically and, in the end, achieved precisely the opposite of what Osama bin Laden had intended.

There are, of course, differences between the post-World War II era and the post 9/11 era. The long-term aftermath of Pearl Harbor was not only a decisive Allied victory in the war but also decades of American leadership and dominance.

After its initial success in Afghanistan following 9/11, victory was not decisive for the United States. Instead, American forces continued to be at war with a number of shadowy jihadist groups, most recently ISIS, and this now seems like a quasi-permanent state of affairs that could persist well beyond the next presidency.

When Congress passed the Authorization for the Use of Military Force immediately after the 9/11 attacks, no one could have imagined this authorization would continue to be the basis for American wars that persist a decade and a half later.

Bin Laden’s hope

Osama bin Laden fervently hoped that attacking the United States would create pressure on American leaders to reduce their support for Middle Eastern regimes. Bin Laden believed that without that American support the Arab regimes would collapse and would be replaced by Taliban-style rulers.

In particular, bin Laden wanted to put pressure on the United States to pull its troops out of Saudi Arabia. Indeed, bin Laden’s principal political goal was to overthrow the Saudi royal family.

On a video that was released four weeks after 9/11, bin Laden made his first public statement since the attacks on New York and Washington, saying “neither America nor the people who live in it will dream of security before we live it in Palestine, and not before all the infidel armies leave the land of Muhammad [Saudi Arabia].”

The video was poorly timed, as it came out on October 7, 2001, the same day the United States began its air campaign against Taliban and al Qaeda targets in Afghanistan.

Two months later the Taliban was completely routed from Afghanistan and within another couple of weeks those key members of al Qaeda who had survived the intense American airstrikes were fleeing to neighboring Pakistan and Iran.

Gambling on weakness

Bin Laden disastrously misjudged the likely American response to the 9/11 attacks because he labored under the delusion that the United States was weak. In his first television interview on CNN in 1997, bin Laden claimed the United States was a paper tiger, pointing to the American withdrawals from Vietnam in the early 1970s, Lebanon in the early 1980s and from Somalia in 1993 as evidence of the United States’ waning power. Bin Laden told CNN, “The US still thinks and brags that it has this kind of power even after all these successive defeats in Vietnam, Beirut … and Somalia.”

Bizarrely, bin Laden believed that al Qaeda’s attacks on New York and Washington would result in an American withdrawal from the Middle East. Instead, the United States quickly toppled the Taliban and al Qaeda – “the base” in Arabic – lost the best base it had ever had in Afghanistan.

In the years after the 9/11 attacks the United States not only did not reduce its influence in the Middle East, but it also established or added to massive bases in Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. And, of course, it also occupied both Afghanistan and Iraq. Bin Laden’s tactical victory on 9/11 turned out to be a spectacular strategic flop.

Since 9/11 the CIA has eliminated many dozens of al Qaeda’s leaders in drone strikes. The CIA also provided the leads that eventually led to the death of bin Laden, when US Navy SEALs raided his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

Meanwhile, al Qaeda has not been able to strike the United States again after 9/11.

A letter written by an al Qaeda member nine months after 9/11 that was addressed to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the operational commander of the September 11 attacks, gives a sense of how much the attacks had backfired: “Consider all the fatal and successive disasters that have afflicted us during a period of no more than six months. … Today we are experiencing one setback after another and have gone from misfortune to disaster.”

Strategic disaster

In 2004 Abu Musab al Suri, a Syrian jihadist who had known bin Laden since the late 1980s, released on the Internet a history of the jihadist movement in which he described the strategic disaster that had engulfed the Taliban and al Qaeda after 9/11: “America destroyed the Islamic Emirate [of the Taliban] in Afghanistan, which had become the refuge for the mujahideen. …The jihad movement rose to glory in the 1960s, and continued through the ’70s and ‘80s, and resulted in the rise of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, but it was destroyed after 9/11.”

Despite the fact that after 9/11 it was obvious to al Qaeda insiders that their organization had taken a terrible beating, Saif al-Adel, one of the group’s military commanders, explained in a 2005 interview that the strikes on New York and Washington were, in fact, a devilishly clever scheme to provoke the United States into making mistakes: “Such strikes will force the person to carry out random acts and provoke him to make serious and sometimes fatal mistakes. …The first reaction was the invasion of Afghanistan.”

There is no evidence, however, that before 9/11 al Qaeda’s leaders made any plans for an American invasion of Afghanistan. They prepared instead only for possible US cruise missile attacks by evacuating their training camps.

Of course, making spectacular errors during a war is a prerogative that all sides enjoy. George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in early 2003 will surely rank as one of the greatest foreign policy failures in American history and it’s hard to imagine that this misadventure could ever have been undertaken at any time other than in the aftermath of 9/11, when the American public was amenable to what the Bush administration was selling as a quick land war in the Middle East that would help curtail terrorism.

The rationales for the Iraq War that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and that he was allied in some manner with al Qaeda were, of course total nonsense.

Rise of ISIS

Worse, the invasion itself led to the creation of al Qaeda in Iraq in 2004, which is the parent organization of what is now ISIS.

When ISIS first gained significant ground in Iraq and Syria in 2014, it focused almost entirely on its actions there and encouraged its overseas followers to join the jihad in the Middle East.

In 2015, ISIS shifted its strategy, attacking on a large scale outside Iraq and Syria. The group claimed responsibility for the downing of the Russian Metrojet carrying 224 passengers and crew on October 31 in the Sinai in Egypt. Two weeks after the Metrojet bombing, a team of ISIS militants attacked multiple locations in Paris.

This marked a pronounced shift by ISIS to directing or inciting operations against the West, but it also underlined ISIS’ incoherent strategy.

ISIS’ main goal is to present itself as the Islamic State that it has named itself, the guardian of an expansive caliphate that is both a theological and a geographic entity. But by attacking Western targets ISIS has united a global coalition against it, which is in the process of thoroughly dismantling the ISIS caliphate.

After ISIS attacked France in November 2015, the French immediately increased their airstrikes on ISIS targets.

Following ISIS’ attacks at Istanbul airport in June 2016, the Turkish army attacked ISIS targets inside Syria, quickly taking the city of Jarablus.

ISIS’ attacks inside Turkey also resulted in a Turkish clampdown on the flow of many thousands of ISIS “foreign fighters,” almost all of whom transited Turkey on the way to join the group in Syria.

ISIS should have understood that provocative attacks against Western targets would only amplify the war against it. As early as summer 2014, following the murder by ISIS of the American journalist James Foley, the United States substantially increased the number of airstrikes against the group and mobilized a coalition of like-minded nations to join the anti-ISIS coalition.

According to U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), nations that have conducted strikes against ISIS – in addition to the United States – are: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Jordan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

ISIS’ terrorist attacks in the West are undermining its overall strategy, which is reminiscent of the mistake al Qaeda made on 9/11, which was to confuse tactical success with strategic victory.

Indeed, according to both Gen. David Petraeus, former US commanding general in Iraq, and Gen Joseph Votel, the commander of CENTCOM, it’s quite possible that Mosul, which is the key city that ISIS holds in Iraq, may fall to Iraqi forces by the end of President Barack Obama’s term in January 2017.

From a purely American perspective, by the time Obama was nearing the end of his second term, the threat from al Qaeda, ISIS and similar groups had receded significantly from its high point on 9/11.

In the past decade and a half since 9/11, 94 Americans have been killed in the United States by jihadist terrorists. Shocking and tragic as these attacks have been, they still pale in comparison to al Qaeda’s murder of almost 3,000 people on the morning of 9/11.