Story highlights

President Obama faces heightened security concerns and a spectacle of admirers that make this trip worlds apart from his previous journeys.

Obama has tried to temper expectations about what he could do for Kenya and its people.

The first time he came to Kenya, they called him Barry.

When he returned 14 years later, they called him senator, but hailed him as more of a king. Thousands of people lined freshly paved roads and sang jubilant songs, including many young boys who were named in his honor.

As Barack Obama arrives in Kenya on Friday for the first time as president of the United States, he faces heightened security concerns and a crushing spectacle of admirers that will make this trip worlds apart from his two previous defining journeys to his father’s ancestral land.

“I’ll be honest with you,” Obama said last week, “visiting Kenya as a private citizen is probably more meaningful to me than visiting as president because I could actually get outside of a hotel room or a conference center.”

His trip to Kenya in the summer of 2006 was part of a 17-day, six-nation tour of Africa that included a visit to his father’s village of Kogelo in the fertile hills of East Africa. It was near that village that Obama was presented a ceremonial goat.

I still remember that day vividly, watching as he tried to politely explain why he couldn’t accept the goat. I was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune back then and explained the scene like this on the front page of the Sunday newspaper on Aug. 27, 2006:

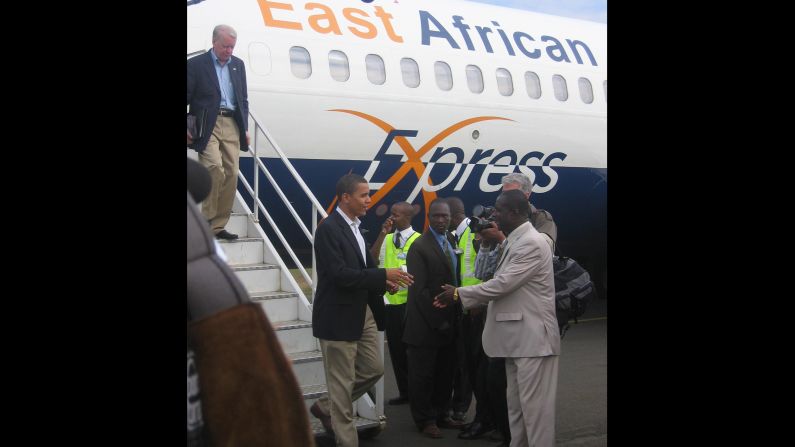

It was a surreal homecoming, Obama said, considering that the last time he came to this part of Kenya he walked a half-mile to the bus depot after taking the overnight train. This time, East African Flight 301 announced his presence to passengers onboard and deposited him a few steps from a waiting caravan.

“Obviously, there’s been a big shift in terms of my travel accommodations,” the Illinois Democrat said. “The last time I arrived in my grandmother’s village, there was a goat in my lap and some chickens.”

This time, the goat came to him.

“We would like to offer you this to signify our appreciation,” said Joshua Monge, keeping a tight grip on the fraying rope looped around the neck of a 3-year-old critter. “It is very fat and very sweet.”

Politely, Obama declined, saying in all seriousness that it was against regulations for him to fly with a goat. So Monge and two friends walked away, convinced that Obama would come back for his goat one day soon.

It’s taken nine years for Obama to return to Kenya, a place to which he has ties like no other because of his father. Obama met him only once, at the age of 10, before he died in a car crash in 1982.

Obama was raised by his Kansas-born mother, Ann Dunham, and his grandparents in Hawaii. But it is the bloodline of Barack Obama Sr. that has stirred so many questions about his roots, fueling a “birther” movement that still simmers today.

His advisers once feared it might keep him from being elected – or re-elected – and he eventually marched into the White House briefing room on April 27, 2011, to present his long-form birth certificate to quiet the controversy stirred by Donald Trump and others.

While Trump is back in the headlines, now running for president himself, the conspiracy surrounding Obama’s heritage is long behind him as he returns to Kenya for what is almost certain to be the only visit of his presidency.

This time, aides said, he is not expected to leave the capital of Nairobi amid fears of terror threats and the shear logistical challenge of visiting such remote terrain around Kogelo, where his step-grandmother still lives.

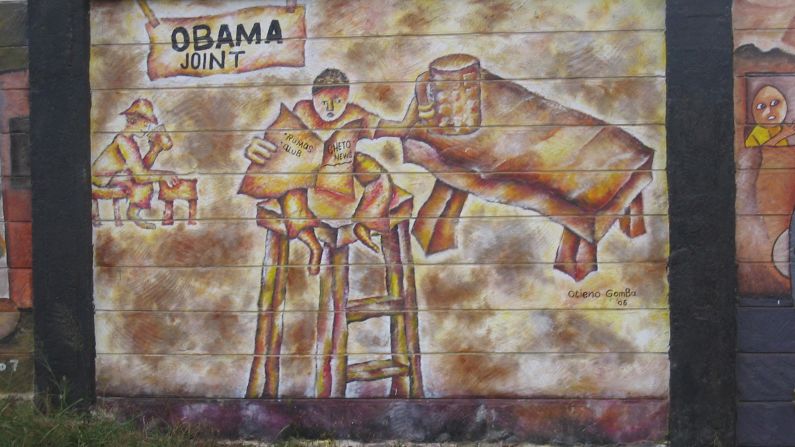

During his visit in 2006, he lingered in Kenya, venturing deep into Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi, delivering an impromptu speech with a bullhorn as throngs of people gathered to see the man they called by only one name: Obama.

“I love all of you, my brothers, all of you, my sisters,” he told the cheering crowd.

But even back then, long before his family’s background was seized upon and scrutinized, Obama tried to temper expectations about what he could do for Kenya and its people. He hinted at his uneasy feelings in the pages of his autobiography, “Dreams From My Father,” which was first published in 1995, nearly a decade before his political rise.

“A part of me wished I could live up to the image that my new relatives imagined for me: a corporate lawyer, an American businessman, my hand poised on the spigot, ready to rain down like manna the largess of the Western world,” a young Obama wrote. “But I course I wasn’t either of those things.”

Now, he’s been most of those things – and more.

As he returns to Kenya on Friday, 28 years after his first visit, the expectations are even higher.

He has been criticized by some for doing less for Africa than his two predecessors, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. He and his aides have rejected that criticism, but his words from a 2006 interview explore the tensions of the weighty expectations.

“Kenya is not my country. It’s the country of my father,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “I feel a connection, but ultimately, it’s not going to be me. It’s going to be them who are climbing a path to improving new lives.”

Obamamania sweeps Kenya as resourceful businesses cash in on visit