Story highlights

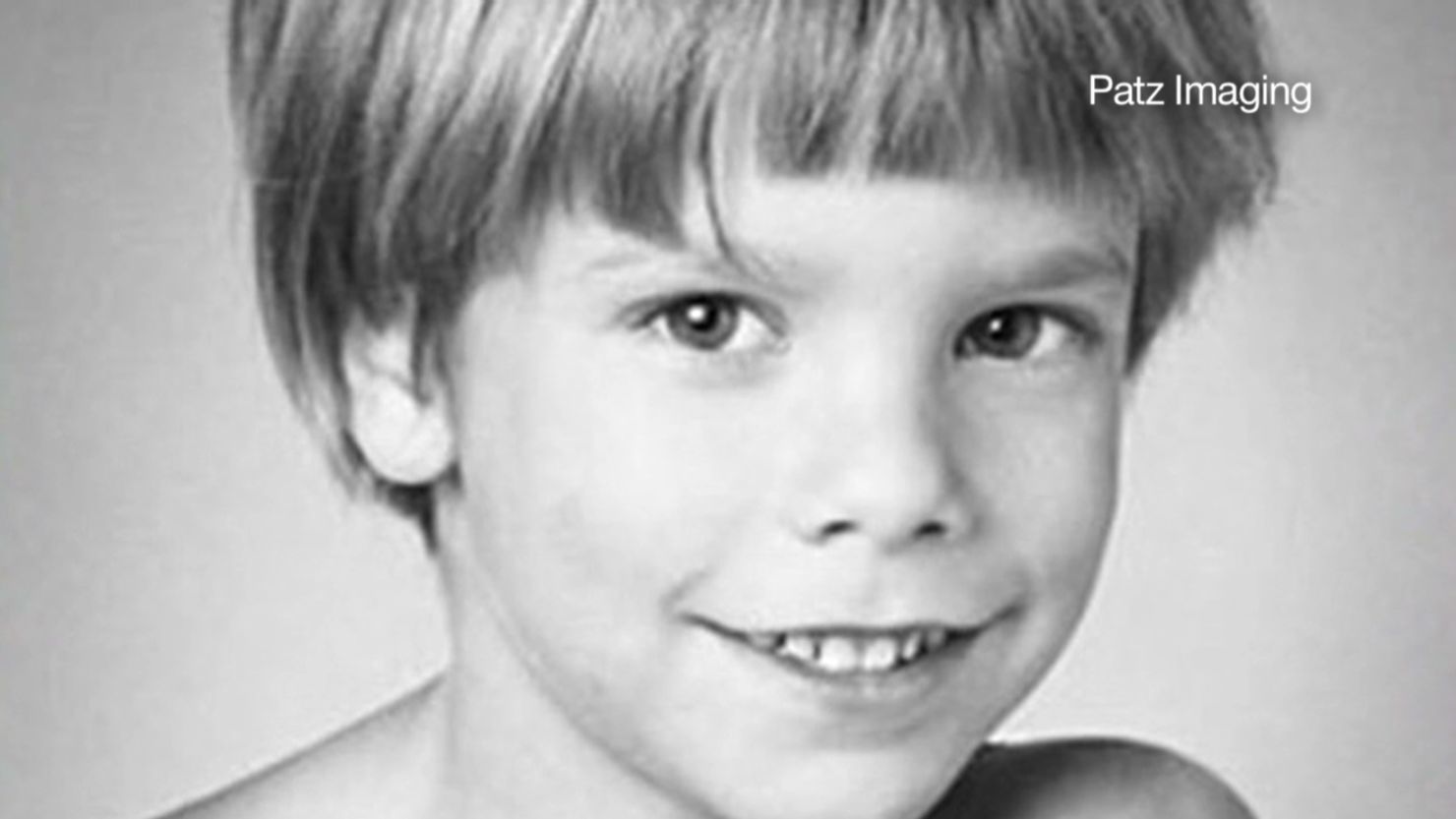

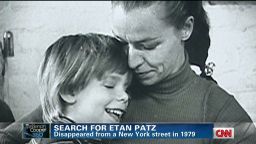

Etan Patz disappeared in 1979; his face appeared on milk cartons all across the United States

His case marked a time of heightened awareness of crimes against children

Pedro Hernandez confessed to the killing three years ago

A New York jury deliberating the fate of the man charged with the 1979 killing of 6-year-old Etan Patz will resume deliberations Thursday, two days after telling the judge it was unable to reach a verdict.

New York Supreme Court Justice Maxwell Wiley on Tuesday afternoon, for the second time in a week, instructed the jury to keep deliberating.

The jury has struggled to reach a verdict since deliberations began on April 15. The case involves a little boy whose disappearance, more than three decades ago, sparked an era of heightened awareness of crimes against children.

As it did nearly one week ago, the jury said in a second note Tuesday that it was unable to reach a unanimous decision on the guilt or innocence of a bodega worker named Pedro Hernandez.

Deliberations had resumed last Thursday after Wiley, using a legal instruction known as an Allen charge, ordered the jury to continue efforts to reach a verdict.

On the 10th day of deliberations, jurors last Wednesday sent their first note declaring an impasse.

Hernandez confessed to police three years ago, but his lawyers said he made up his account of the crime.

Severe mental illness?

Etan’s parents have waited more than 35 years for justice, but some have questioned whether that is even possible in Hernandez’s case. His lawyer has said he is mentally challenged, severely mentally ill and unable to tell whether he committed the crime.

Hernandez told police in a taped statement that he lured Etan into a basement as the boy was on his way to a bus stop in Lower Manhattan. He said he killed the boy and threw his body away in a plastic bag.

Neither the child nor his remains have been recovered.

Hernandez has been diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder, one of a group of conditions informally thought of as “eccentric” personality disorders. He has an “IQ in the borderline-to-mild mental retardation range,” his attorney Harvey Fishbein has said.

A long interrogation

Police interrogated Hernandez for 7½ hours before he confessed.

“I think anyone who sees these confessions will understand that when the police were finished, Mr. Hernandez believed he had killed Etan. But that doesn’t mean he actually did, and that’s the whole point of this case,” Fishbein has said.

In November, a New York judge ruled that Hernandez’s confession and his waiving of his Miranda rights were legal, making the confession admissible in court.

Hernandez is charged with two counts of second-degree murder for allegedly intending to cause the boy’s death and for a killing that occurred during a kidnapping.

Another suspect?

Another man’s name has also hung over the Etan Patz case for years: Jose Antonio Ramos, a convicted child molester acquainted with Etan’s babysitter. Etan’s parents, Stan and Julia Patz, sued Ramos in 2001. The boy was officially declared dead as part of that lawsuit.

A judge found Ramos responsible for the boy’s death and ordered him to pay the family $2 million, money the Patz family has never received.

Though Ramos was at the center of investigations for years, he has never been charged. He served a 20-year prison sentence in Pennsylvania for molesting another boy and was set to be released in 2012.

He was immediately rearrested upon leaving jail in 2012 on charges of failing to register as a sex offender, The Associated Press reported.

Dawn of child protection

Since their young son’s disappearance, the Patzes have worked to keep the case alive and to create awareness of missing children in the United States.

In the early 1980s, Etan’s photo appeared on milk cartons across the country, and news media focused on the search for him and other missing children.

“It awakened America,” said Ernie Allen, president and chief executive officer of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. “It was the beginning of a missing children’s movement.”

The number of children who are kidnapped and killed has remained steady – it has always been a relatively small number – but awareness of the cases has skyrocketed, experts said.

The news industry was expanding to cable television, and sweet images of children appeared along with distraught parents begging for their safe return. The fear rising across the nation sparked awareness and prompted change from politicians and police.

In 1984, Congress passed the Missing Children’s Assistance Act, which led to the creation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

President Ronald Reagan opened the center in a White House ceremony in 1984. It soon began operating a 24-hour toll-free hot line on which callers could report information about missing boys and girls.

CNN’s Ben Brumfield, Lorenzo Ferrigno and Joe Sterling contributed to this report.