Story highlights

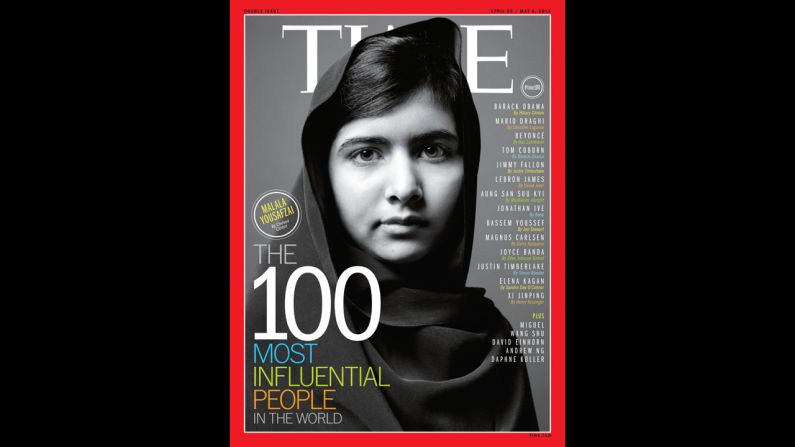

Malala Yousafzai becomes the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize

Taliban gunmen stopped a van carrying Malala and shot her two years ago

The extremists wanted to kill her for promoting education for girls

There was a global outpouring that propelled her and her cause onto the global stage

On Friday, Malala Yousafzai became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. But just a day earlier, she passed the two-year anniversary of the gruesome event that flung her and her cause onto the world stage – the attempt on her life.

Malala was riding home from school on Tuesday, October 9, 2012.

Gunmen halted the van ferrying her through her native Swat Valley, one of the most conservative regions in Pakistan. They demanded that other girls in the vehicle identify her. Malala had faced frequent death threats in the past.

She was pointed out. At least one gunman opened fire, wounding three girls. Two suffered nonlethal injuries, but bullets struck Malala in the head and neck.

The bus driver hit the gas. The assailants got away.

Malala was left in critical condition. An uncle described her as having excruciating pain and being unable to stop moving her arms and legs.

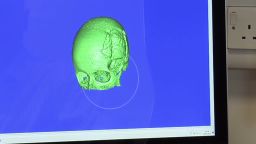

Doctors fought to save her life, then her condition took a dip. They operated to remove a bullet from her neck, and extracted a piece of skull to relieve pressure on Malala’s brain because of swelling. After surgery, she was unresponsive for three days.

Recovery in the UK

Malala was taken by helicopter from one military hospital in Pakistan to another, where doctors placed her in a medically induced coma so an air ambulance could fly her to Britain for treatment.

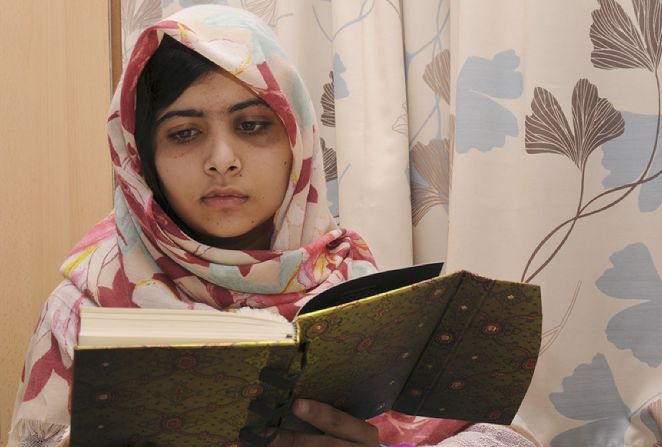

Little more than a week after being shot a world away, Malala got back on her feet again, able to stand when leaning on a nurse’s arm at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England.

It was nothing short of a miracle that the teen blogger, who fought for the right of girls to get an education, was still alive and even more astounding that she suffered no major brain or nerve damage.

Less than three months after being gunned down, she was discharged from the hospital to continue her rehabilitation at her family’s new home. A groundbreaking surgery later repaired the damage to her skull.

Malala a global movement

Beyond her hospital room, a world sympathetic to her ordeal has transformed her into a global symbol for the fight to allow girls everywhere access to an education.

The bloodletting sparked outrage inside Pakistan against the radical Islamist group, which continues to wield influence in parts of the country. Around the world, the young blogger became a poster child for a widespread need to permit girls to get an education.

In Pakistan, the airwaves filled with leaders and commentators who publicly got behind her, and journalists closely followed her story, drawing death threats from the Taliban for their coverage.

Her story spread around the world, and world leaders took up her cause, particularly former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

The United Nations launched a campaign for girls’ education named “I am Malala,” which Brown guided as special envoy on global education. And it declared November 10 Malala Day – a day of action to focus on “Malala and the 32 million girls like Malala not at school.”

Malala’s activism goes on

Malala founded the Malala Fund, which invests in local educational initiatives for girls in Pakistan, Nigeria and Kenya, and in Jordan, where it focuses on Syrian refugees.

And she continued to advocate around the world for a girl’s right to an education, speaking before the U.N.

Last year, she was a contender for the Nobel Peace Prize, but did not win. She was modest about her prospects then, saying a win would be premature.

“I think that it’s really an early age,” Malala said. She wanted to do more to earn it first.

“I would feel proud, when I would work for education, when I would have done something, when I would be feeling confident to tell people, ‘Yes! I have built that school; I have done that teachers’ training, I have sent that (many) children to school,’ ” she said.

“Then if I get the Nobel Peace Prize, I will be saying, Yeah, I deserve it, somehow.”

Last year, she also was awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought from the European Parliament, and she published her autobiography, “I Am Malala” on her struggle to get an education.

World support for her cause has not deterred the Taliban from pursuing her death.

After her book’s publication, they renewed their threat. They also vowed to attack any bookstore that sold it.

Extremists out to get her

Malala’s struggle for education for girls and against the Pakistani Taliban predates the attempt on her life.

Since she was 11, with the help of her father, a schoolteacher, she had encouraged girls and their families to resist extremists who pushed girls from classrooms.

In January 2009, the militants issued an edict ordering that no school should educate girls. Malala wrote in her online diary, published by the BBC, about intimidation tactics the Taliban used in the Swat Valley in northwest Pakistan to coerce girls into not going school.

They included house raids to search for books, and Malala had to hide hers under her bed.

The extremists took issue with her blogging and issued the first threats to kill her.

“I was scared of being beheaded by the Taliban because of my passion for education,” she told CNN three years ago. Despite her fears, she stayed in the public eye, giving media interviews about her struggle for education in the face of oppression.

Friday’s peace prize may be the most prestigious Malala has received, but it is not her first. At home, her writings garnered her Pakistan’s first-ever National Peace Prize in late 2011.