Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world.

Story highlights

Guinea worm disease once infected millions -- now it's almost eradicated

But finding the remaining cases will be a challenge

There is no vaccine -- beating the disease involves education and improved sanitation

“It’s such a loser of a disease that some countries eradicated it without even knowing they’d had it. It can naturally disappear.”

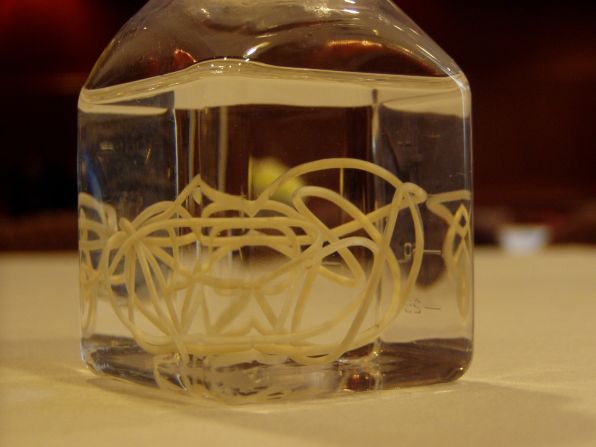

The disease Sandy Cairncross of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is referring to is Guinea worm, a condition that culminates in a worm up to 3 feet long bursting out of your skin, often unbeknownst to the person it’s bursting out of until it’s about to happen.

It’s something a picture could never prepare you for, and loser or not, this agonizing illness was infecting millions of people just 30 years ago. But thankfully it’s a disease that’s next on the cards for global eradication.

“There is no treatment or vaccine. Its eradication involves simple interventions such as clean water and sanitation and the use of community health teams,” explains Cairncross, a water engineer by background and now professor of environmental health.

Burning pain

People become infected with Guinea worm after drinking water contaminated with the larvae of the parasitic worm Dracunculus medinensis, typically in remote rural areas. The larvae then grow in the host into adult worms over the course of one year, at which point females burst out of their host’s foot or leg to lay eggs. The eggs need to be laid in water and as people stand in their shallow dug-out wells to collect their daily water supply, or to relieve the terrible burning of the residing worm, the worm seizes the opportunity and contaminates the village water supply in the process.

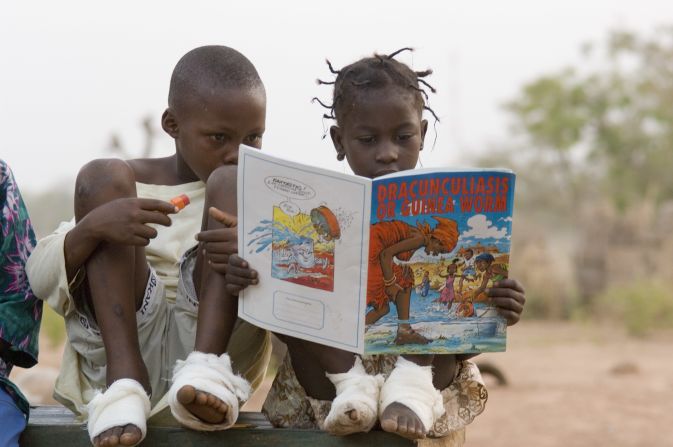

It’s rarely fatal but patients often remain sick for several months, meaning they can’t work, which impacts their income and the local economy. The only “treatment” is the extraction of the worm from a patient’s leg, which is then bandaged to enable recovery.

Cairncross has been involved with the global Guinea Worm Eradication Program (GWEP) since the early 1990s when he joined UNICEF to target the disease in West Africa. “Guinea worm is extremely rural and is found in the poorest parts of Africa, where health services simply don’t reach,” he says. It’s a disease of poverty.

Read: This machine makes drinking water from thin air

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) initiated GWEP in 1980 off the back of the success of the smallpox eradication campaign. Since the disease is solely spread by contaminated water, the program was used as an indicator for the United Nations 1981-1990 International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (IDWSSD), and large-scale advocacy for the campaign began in 1986 when the Carter Center got involved.

The Carter Center is led by former U.S. president Jimmy Carter, who wanted to use his status to broker peace and fight disease worldwide. Since 1982 the center has operated with a mandate to resolve political conflict and combat disease. Guinea worm factors in both.

The final cases

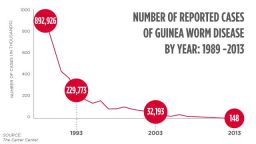

Since 1986, numbers have plummeted from 3.5 million cases across 21 countries in Asia and Africa to just 148 cases in 2013 in four remaining countries – Chad, Ethiopia, Mali and South Sudan, where the majority of cases lie. The challenge now is finding those last cases because with eradication, “the nearer you get, the harder it gets,” says Cairncross. “The cases left are either unreachable, or forgotten,” he adds.

Guinea worm, sometimes known as the “fiery serpent,” is not on the radar of most Western governments, especially with so few cases remaining worldwide causing the “cost per case” to increase dramatically.

“A million-dollar case search in Guinea once found only one case of the disease, which had been imported,” says Cairncross. But aside from these costs for surveillance, the control of the disease itself is simple: clean water and education.

“It is a matter of education,” explains Dr. Ernesto Ruiz-Tiben, who directs the Carter Center’s program.

A crucial aspect of disease control is teaching locals to filter their water with basic nylon filters and to avoid standing in water when infected. People are encouraged to strain water through nylon filters, or even clothing material, to remove the worm’s larvae before they drink it. The shallow nature of the muddy watering holes people use means they frequently stand in them when collecting water.

In the fight to educate, the real progress has been made using local villagers. The program pioneered the role of the “community health worker,” who are now commonplace for a variety of global health programs.

The extreme rural nature of Guinea worm means those leading the programs cannot be in the field enough to monitor the disease closely. A large proportion of the control efforts are therefore run by local volunteers and community teams who act as surveillance units, keep an ear out in their local village to see who may be infected and supply people with filters at water collection points.

“As communities learn about the worm and its life cycle, they discover that they can get rid of it by themselves. We give them the lessons, but they do the work,” says Ruiz-Tiben. “That’s why it can be eradicated worldwide.”

The intended date to reach eradication was 2015. “Previous targets were 1995, then 2000, now who knows?” explains Cairncross. “We need local government backing, funding and commitment.”

The disease can also re-emerge due to negligence and insecurity during conflict, which is why the majority of cases now occur in South Sudan. In 2007 an outbreak occurred in Ghana due to government officials allowing a water supply to degrade and become infected. Although cases are now few, if left the disease can return and spread making the hunt for the last cases all the more important.

Ruiz-Tiben is determined to find these cases and remove the disease from our planet once and for all. “We’ll be standing until the last worm goes,” he concludes.

Read: From toilet to tap – drinking recycled waste water