Editor’s Note: Kenneth V. Lanning, a consultant in crimes against children, was a special agent with the FBI for more than 30 years and was assigned to the FBI Behavioral Science Unit at the FBI Academy for 20 of those years.

Story highlights

Kenneth Lanning: It is almost miraculous that three women missing for a decade turned up

Lanning: Long-term missing cases are the most difficult and draining for law enforcement

He says majority of missing kids go missing because they were runaways, lost or injured

Cleveland case inspiring, but most long-term abduction cases don't end happily, he says

It is almost miraculous that three women who have been missing for a decade have turned up. The story of Amanda Berry, who screamed for help and got the attention of a neighbor who broke down a door that set her and two other women free, is riveting. Police have already arrested three suspects.

As details emerge in the coming days, many people are asking: How could something like this happen? Why did the police not find them earlier? There are far more questions than answers at this point.

Although the terms abduction and missing have become almost synonymous, they are not quite the same.

In sexually motivated abduction cases, the child is usually returned before anyone had time to note the child was even missing. The motivation is easier to evaluate, and the investigation usually focuses primarily on any sexual assault.

In long-term missing/abduction cases, the motivation is harder to evaluate, and the investigation usually focuses more on finding the “missing” child. Such cases are among the most difficult, frustrating and emotionally draining for law enforcement.

Children can be missing for a wide variety of reasons (e.g., runaway, throwaway, lost, injured, etc.) other than abduction and can be abducted for a wide variety of motivations (profit, ransom, custodial disputes, etc.) other than sex.

For long-separated families, reunions can be a struggle

What investigators are often presented with is simply the fact that a child is missing – the child did not return home as expected. Family and friends want an immediate and aggressive response by law enforcement with the issuing of Amber Alerts.

Law enforcement, however, must consider and evaluate all possibilities. Especially in cases involving teenagers or families living a chaotic lifestyle, determining that an abduction even took place can be difficult. It is simply not possible or reasonable for law enforcement to respond to every missing child case as if it were a sexually motivated nonfamily abduction.

The vast majority of missing children are missing because they were runaways, lost, accidentally injured or gone for a variety of benign reasons (e.g., lost track of time). A runaway or lured-away child, however, can easily become an abducted child when prevented from returning home.

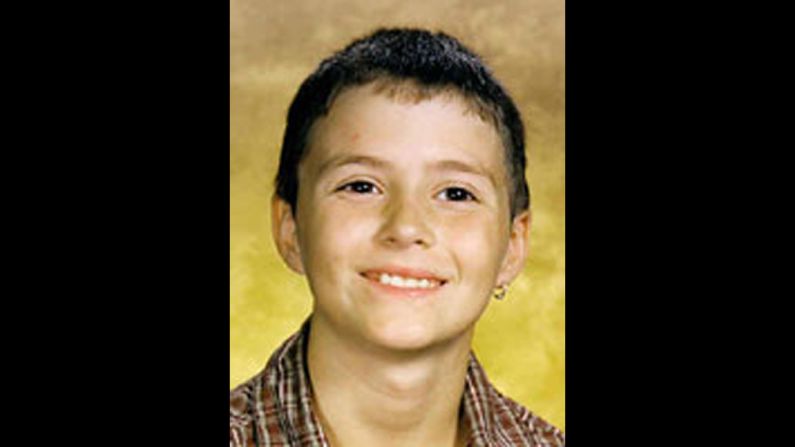

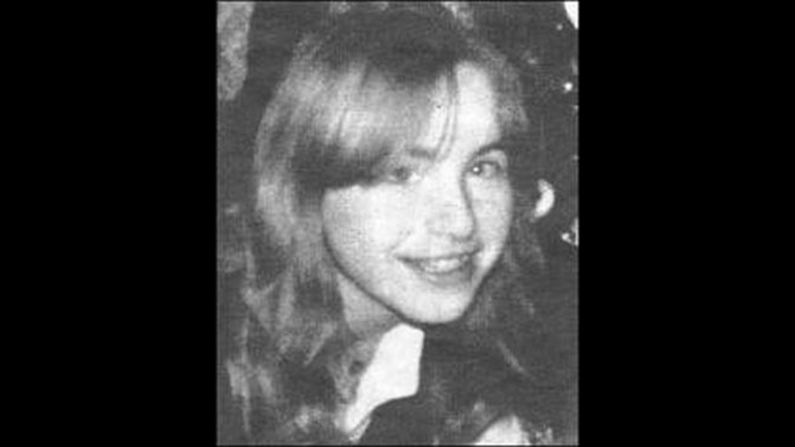

In sexually motivated abduction cases, a child will usually be held only long enough for the offender to engage in some amount of sexual activity. A few sex offenders, however, seem to want to believe they will live happily ever after with their abducted victim as a sex partner. In a few cases (e.g., Elizabeth Smart, Tara Burke, Jaycee Dugard, Shawn Hornbeck and Steven Stayner) victims have surfaced alive many months or years after being abducted. Many parents of long missing children understandably pray that their children are among such victims.

In cases in which the victims are held and kept alive long term, the offender must have a method of control beyond just typical threats and violence. In my experience, this has sometimes involved the assistance of one or more accomplices or the use of physical controls such as a remote location, soundproof room, underground chamber or elaborate restraining devices.

It also usually involves an evolving and changing relationship between the offender and the child victim. The offender gradually moves from being a stranger using force to an acquaintance using seduction to a father-like or domestic figure using a family-like bond.

In some cases in which I have been involved, victims have been left alone, were poorly guarded, did not try to escape or seemed almost compliant in a variety of ways in their victimization. Victims may even feel guilt, shame and embarrassment or blame themselves as a result of this. In my opinion, the victims who survived the odds did the right thing, whatever it was. The Patty Hearst case is one in which society and the criminal justice system struggled with abduction victim accountability for behavior that helped lead to survival.

Some prefer to explain this as being the result of a mysterious process called “brainwashing” or the “Stockholm Syndrome.” I see it as a perfectly understandable result of adult/child interaction and influence over time. A survival and interdependency bond may develop. It is a kind of adaptation or learned helplessness. This process can vary significantly based on the personality characteristics of both the offender and victim.

The case of the three Cleveland women who have escaped their captor after so long is inspiring and offers hope for other cases. But most long-term nonfamily-child abduction cases, unfortunately, do not have such happy endings. However, that should not prevent the continuing efforts to resolve them. The greatest accomplishment of almost any law enforcement investigator would be to be able to return a missing child to his or her parents.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Kenneth V. Lanning.