Editor’s Note: Roland Martin is a syndicated columnist and author of “The First: President Barack Obama’s Road to the White House.” He is a commentator for the TV One cable network and host/managing editor of its Sunday morning news show, “Washington Watch with Roland Martin.”

Story highlights

Roland Martin: The 50th anniversary of the March on Washington is coming up

Martin: In two-thirds of the "I Have a Dream" speech, King focused on economic issues

Today, black unemployment is high, and black income levels are low, he says

Martin: In commemorating the march, organizers must focus on economic challenges

It is always important to look back on historical moments in history and remember how it was and reflect on those who made it possible. But it is also vital to continue having a forward-looking vision that connects the past with the present.

When veterans of the civil rights movement and those who weren’t even alive in the 1960s pick a date and gather in Washington to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a lot will be said about the past.

Rep. John Lewis of Georgia is the only surviving speaker on the official part of the program, and others who witnessed the speech are older and grayer but still among us.

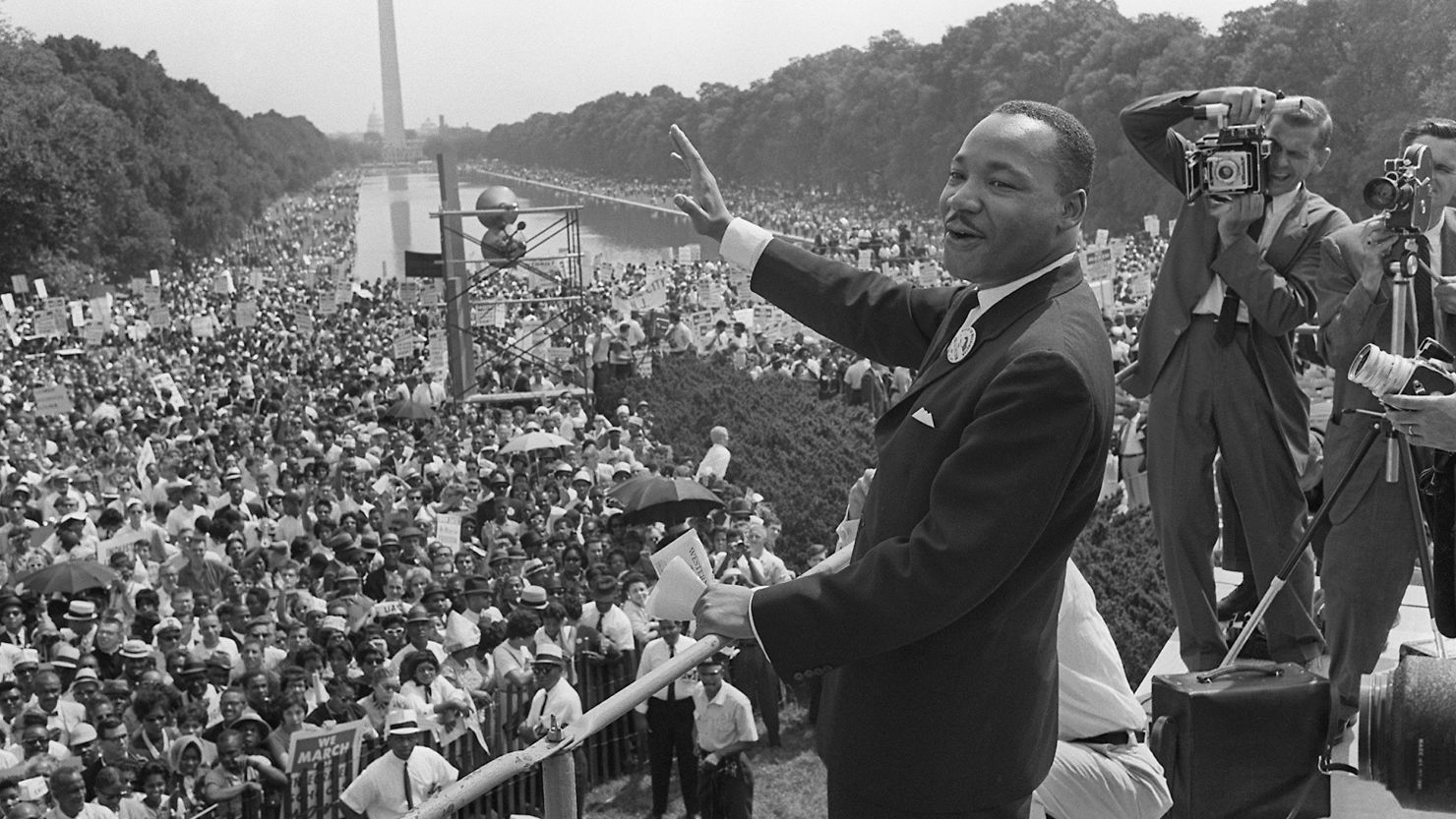

It must have been an unbelievable sight to see about 250,000 people before the Lincoln Memorial to gather for jobs and freedom for African-Americans on August 28, 1963. We remember the march because of the massive audience as well as the culmination of that day, the riveting speech of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered what is known today as the “I Have a Dream” speech.

During that moment in history, the heavy hand of Jim Crow was oppressive for African-Americans all across America but especially for those living under the brutality in the South. Voting was virtually nonexistent. Blacks couldn’t eat in public places like hotels and restaurants. But what the march largely focused on was the economic condition of African-Americans.

Get our free weekly newsletter

When most folks think about the march, too much focus is on the “I Have a Dream” portion of King’s speech and not the top two-thirds, which was a condemnation of the economic policies that stifled black growth in America.

“One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination,” King said. “One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.”

What many people forget is that in the final year of his life, King was planning the Poor People’s Campaign, looking to focus the nation on its poorest citizens. King confidant Harry Belafonte told me last year for an interview on my TV One show, “Washington Watch,” that King understood that black America, and all Americans, couldn’t be truly free unless they had economic freedom.

A lot has changed for black America since August 28, 1963, but when you examine the economic condition in 2013, we are still facing troubled times.

As America has desperately tried to escape the recession that gripped the world over the past few years, black unemployment remains pathetically high. Overall, the unemployment rate announced in March was 7.7%. For African-Americans, it was 13.8%. Black teen unemployment was 43.1%.

The wealth gap between whites and blacks is even wider today than it has been in three decades.

According to a recent report (PDF) released by Brandeis University, the wealth gap between whites and black increased from $85,000 to $236,500 between 1984 and 2009.

The median net worth of white families is now $265,000, and it’s $28,500 for black families.

The Brandeis study says there are five vital factors for this: number of years owning a home, average family income, college education, employment stability, and financial support from families and inheritance.

Many will read this and say, “Oh, please! Get an education, find a good job, work hard, and all will be well.”

But it’s not as simple as that. When you look at the state of education where African-Americans largely live, resources play a crucial role in all of this. The lack of a quality education plays a role in what college you’re able to attend, and that will determine what kind of job you will have.

The long-term racial policies of America have also played a role. The failure of black families being able to go to college for decades in the 20th century, as well as access to good-paying jobs, has played a role in the inability of blacks to pass down wealth from one generation to another.

All of these factors are why a commemoration of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom shouldn’t be a big love-fest for folks focused on civil rights. It should be singularly focused on driving an agenda that speaks to the unemployment crisis afflicting black America.

Those who are planning events around the march shouldn’t fall into the easy trap of letting any and everyone bring their agenda in August. The beauty of the 1963 march is that it was narrow, specific and designed to address a critical need.

If organizers today want to really walk in the footsteps of those in 1963, they should go back and study why they all met in the first place. The agenda was set in 1963 on jobs and income inequality. In 2013, this generation should pick up that baton and run with it so that the next time there is a commemoration, we will be celebrating how successful we were in addressing and fixing the problem.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Roland Martin.