Story highlights

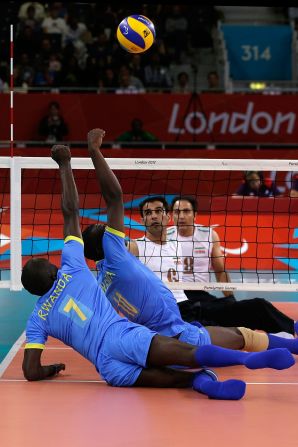

CNN talks to the Rwandan sitting volleyball team before the London Paralympics

The team is made up largely of amputees from the 1994 genocide

Up to a million people were killed in violence between Hutus and Tutsis

Now soldiers who once fought against each other play on the same team

The small group of young men walk confidently into the gymnasium in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, sit down and casually unfasten their legs.

Each prosthetic limb is of differing sizes and shapes. Some are adorned with Nike trainers, others Puma. Each is left abandoned by the wheelchairs that circle the small volleyball court drawn out on to the hard concrete surface as their owners take to the floor and artfully glide into position.

It has been a tough month for the Rwandan sitting volleyball team. Every day has seen double practice sessions. They have the biggest matches of their lives to prepare for: a Sub-Saharan qualification tournament against the likes of Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

It is due to take place on home soil, in Kigali, and the Rwandans are the favorites. But it’s not local bragging rights at stake. The winner secures a place at the 2012 London Paralympics.

Rwanda is a country that is still synonymous with the 1994 genocide that saw the slaughter of close to a million people in eight months during a civil war between the dominant Hutus against the minority Tutsis.

Follow CNN’s Paralympics live blog

Today the country is still in the process of rebuilding from that brutal, almost unimaginable horror. But there is one sign of the genocide that cannot be erased so easily. The hundreds of thousands of amputees left maimed, but who survived the violence, who move silently through the crowded markets and streets like apologetic ghosts; unseen and unheard. No one talks of the genocide any more. But the amputees remain a record of the country’s horrific past.

It is a situation that the young men sitting on the floor practicing sitting volleyball are only too aware of.

“I started in 2009 and saw the game and I wasn’t comfortable with it, but after a year I saw it was a good game for people with disabilities,” said 25-year-old university student Emile Vuningoma, who plays as an attacker in the team, as he took a break from training in the dark hall.

Join the Paralympics conversation #cnnparalympics

Vuningoma was born with his disability, but his parents didn’t have the money to pay for the medical treatment that might have allowed him to use his leg. Playing for the team has given him a sense of purpose that many disabled people in Rwanda have yet to find.

“To be at London is very important for people with disabilities in Rwanda because we have to be there to present our country to the people with disabilities and those without disabilities,” he said.

“There are some people in Rwanda who have the injuries from the 1994 genocide and do not have the capabilities to be part of society. They think about the past. There are so many with disabilities from the 1994 genocide. We are working hard to go to all the provinces and ask them to come back.”

Laying ghosts to rest

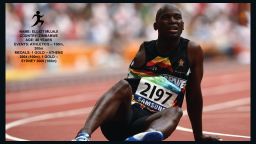

One player who was directly affected by the genocide was the team’s captain Dominique Bizimana, who is also the head of the Rwandan Paralympic Committee.

“There was the genocide and we were young, there was mines and by bad chance I lost my leg when I was 16,” he explained.

“I was a volleyball player before I lost my leg. But when I lost my leg I said, ‘No, I cannot give up. I have to fight to play sports.’ And I started to play sitting volleyball in 2004. We are lucky because sports is one of the only ways to integrate people with disabilities (into society). We use sports as one way to do this.”

Sport has also offered Bizimana the chance to lay to rest some of his own ghosts. During the genocide he was a 16-year-old conscript in a Tutsi militia. Playing next to him at the London 2012 Paralympic Games is 48-year-old Jean Rukondo, who fought against him in the Hutu-dominated army. Both lost a leg in the fighting but are now on the same team and best of friends.

Training begins. The players move quickly across the floor at breakneck speed, careful to keep part of their backside and thigh on the floor at the same time (the main rule in sitting volleyball). Standing over them is Peter Karreman, the team’s Dutch coach who masterminded Rwanda’s qualification to the world championships last year. They lost every game, some heavily, but the experience ahead of the the Sub-Saharan qualification tournament was invaluable.

“About eight years ago I was training regular volleyball and by coincidence I saw sitting volleyball and it got me, it hit me in my heart. I became the head coach of Dutch team. Then the Rwanda team asked me,” he said outside the hall.

Many challenges

Unlike some disability sports, sitting volleyball is so tough to master, and so fast, that the technique of some of the top players is better than those in the able-bodied game.

“The rules are the same, but the term sitting is not good. They are moving on the ground, moving moving,” explained Karreman. “The rest of the game is the same. But it is fast, the field is smaller. So it’s very attractive. It’s good to play for the regular players because they learn how to play fast as well. It’s good for their technique.”

But preparing the team for the Paralympics has been Karreman’s hardest job yet. The facilities are austere. In the corner stands a heap of twisted wheelchairs. The showers have long run dry. And the floor is so hard that Karreman is surprised the Rwandan team are happy to play on it. “In Europe they would refuse to play on a floor this hard,” he said.

Real progress needs more funds. “To get them really improved they need money. It is still a problem.”

The difficulties were highlighted a few weeks earlier when it was revealed that the Rwandans were still almost $5,000 short for hosting the qualification tournament and were close to canceling it, and with it the team’s Paralympic dream. Instead the British High Commissioner for Rwanda stepped in and found the cash.

“They have their (the government’s) attention now,” said Karreman before going back to his players for another grueling training session “This will give a boost for the rest for the country that Rwanda is in London with this team.”

‘Disability is nothing’

The tournament went ahead, and Rwanda stole the show. They won every game, conceding just once, beating Kenya in the final 3-0 and qualifying for the Paralympics. They are still a long shot for a medal. As the coach points out , they would have to “train 48 hours a day” to get close.

And other problems have arisen. The Rwandans had to cancel another regional tournament due to a lack of funds, a typical occurrence in African disability sport. Yet Bizimana believes that their appearance in London can send a message to those still struggling to come to terms with how their lives have changed forever in 1994 – a message that resonates far outside this tiny, scarred African state.

“It is very difficult to have confidence, to accept what happened. Some people don’t have. They are still fighting it,” said Bizimana.

“I think we are superstars. For us disability is nothing. We are able. We are making sure we tell people disability is nothing. It is not inability.”